By Peggy Butler

Special to the Journal

So who named them Oystercatchers?

They don’t catch oysters or even prefer them for dinner. And whoever named anything oystercatcher has never caught oysters, because you don’t.

You put on big rubber boots, wade into thick mud at the water’s edge and step between slick rocks, risk broken ankles or cracked knees to pick them. Or you tong them with long ‘rakish’ like tongs — from a boat — or dredge them with a weighted net if you are a very serious oystermonger.

There is no chasing or lying in wait to get your oyster.

Oystercatchers eat little shellfish like mussels, chitins and limpets according to Wikipedia, which knows everything. Some of them may eat oysters sometimes.

I am writing about oystercatchers because I want to nominate them for a parenting award.

Most small birds take only a few weeks to become independent, which means they can get food for themselves. At our house we call it “FFY,” which means “fend for yourself.”

Very large birds, like eagles, may actually teach their offspring to hunt. For the hunting-challenged this may take a few months.

But oystercatcher parents must work tirelessly for a year teaching by example how to hunt and husk while they feed the oystercatcher kids already peeled bivalves and mollusks from their own plates.

Baby oystercatchers cannot hunt and gather like an oystercatcher. They must be trained and protected.

What could happen? An inexperienced fledgling may get his or her beak caught between the two powerful half shells of a bivalve as it quickly snaps shut. How would one even call for help?

Little oystercatcher kids would be clasped tight by the beak as the tide comes and perhaps drown without a peep.

According to Greg Laden’s science blog, the young birds have a weak and ineffective beak for about a year. Gradually the beak becomes hard, sharp, double-edged and long, and effective for prying open bivalves.

In the meantime, they follow their mother around constantly observing how she gets food. By the time their beak grows to an amazing 4.5-inches long, they know how to chisel into food stores by themselves.

The conscientious oystercatcher parents tend their young until that happens. That may be why they don’t migrate.

Anyway, how would you manage helpless and bored fledglings while traveling? (“Mommy, he’s flying in my air!’). Mostly they like to stay home all year close to food and family, which makes them my kind of bird.

A recent survey suggests that there are a total of 210 nesting oystercatcher pairs living on rocky coves in the whole of the Salish Sea. They are being studied by all kinds of agencies in British Columbia, San Juan Islands, and Alaska.

They stay married for as long as 20 years. That’s the longest recorded pair.

They set up housekeeping by scraping out a little indentation in the rocks and lay their eggs, probably two, sometimes three.

Two is better. Have you ever talked to a mother with three children?

Three is not a good number — someone is always left out. There is fighting and hurt feelings. But then it does give you a spare if something bad happens.

Speaking of bad things happening—this spring I saw a fox rushing down and around the rocks at water level and I was amazed at his dexterity. I wondered what he was doing.

Back to nests. The nest is for sitting on eggs, which have inside cushioning so they don’t mind the rocky indentation.

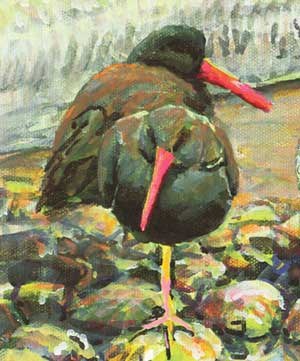

The oystercatcher does not sleep in a nest. It sleeps with one pink leg grasped to a rough rock while hitching up the other somewhere warm while it tucks its head and unwieldy beak under a wing. From my own observations I can tell you that they select safe off shore rocks to sleep on.

So far I have not seen a fox swim out to get one.

So, who named the oystercatcher?

It was John James Audubon himself, along with his friend John Bachman, in 1838. Apparently, neither of them studied oysters.

It may not be a very accurate sort of name, but you have to admit — it is catchy.

If you would like to see four or five of the 210 oystercatcher couples of the Salish Sea, take a walk along the coves at American Camp, on San Juan Island. Watch the low rocks nearest the shoreline.

If you would like to see an oystercatcher in your own living room, you can look up “racerocks preserve” on the internet. You can watch them feed, hatch, and mate.

Apparently, privacy is not for the birds. A large round unblinking eye will stare back at you.

— Peggy Butler and family, island residents, enjoy the many sights of San Juan Island, migratory and native. Read Butler’s two-part series on out-of-state license plates in the Sept. 7 and Oct. 19 editions of the Journal.