She was beaten by the San Francisco police so badly during a protest in 1988, that she was hospitalized with three broken ribs and her spleen removed. Thirty years later, civil rights leader Dolores Huerta still fights for the people.

“She is the most important and least known activist,” said Danna Diaz, San Juan Island School District superintendent to the hundreds of islanders who came to watch Huerta’s documentary “Dolores” on Jan. 29 at the San Juan Community Theatre. The event, sponsored by both the Friday Harbor Film Festival and Soroptimist International of Friday Harbor, was free with donations going toward the Dolores Huerta Foundation. This foundation is a nonprofit that funds grassroots efforts for education, voting registration, and encouraging people, especially women, to run for government positions, Huerta told the Journal. It also supports an array of social justice issues including the rights of Native Americans, African Americans, women and the LGBTQ community.

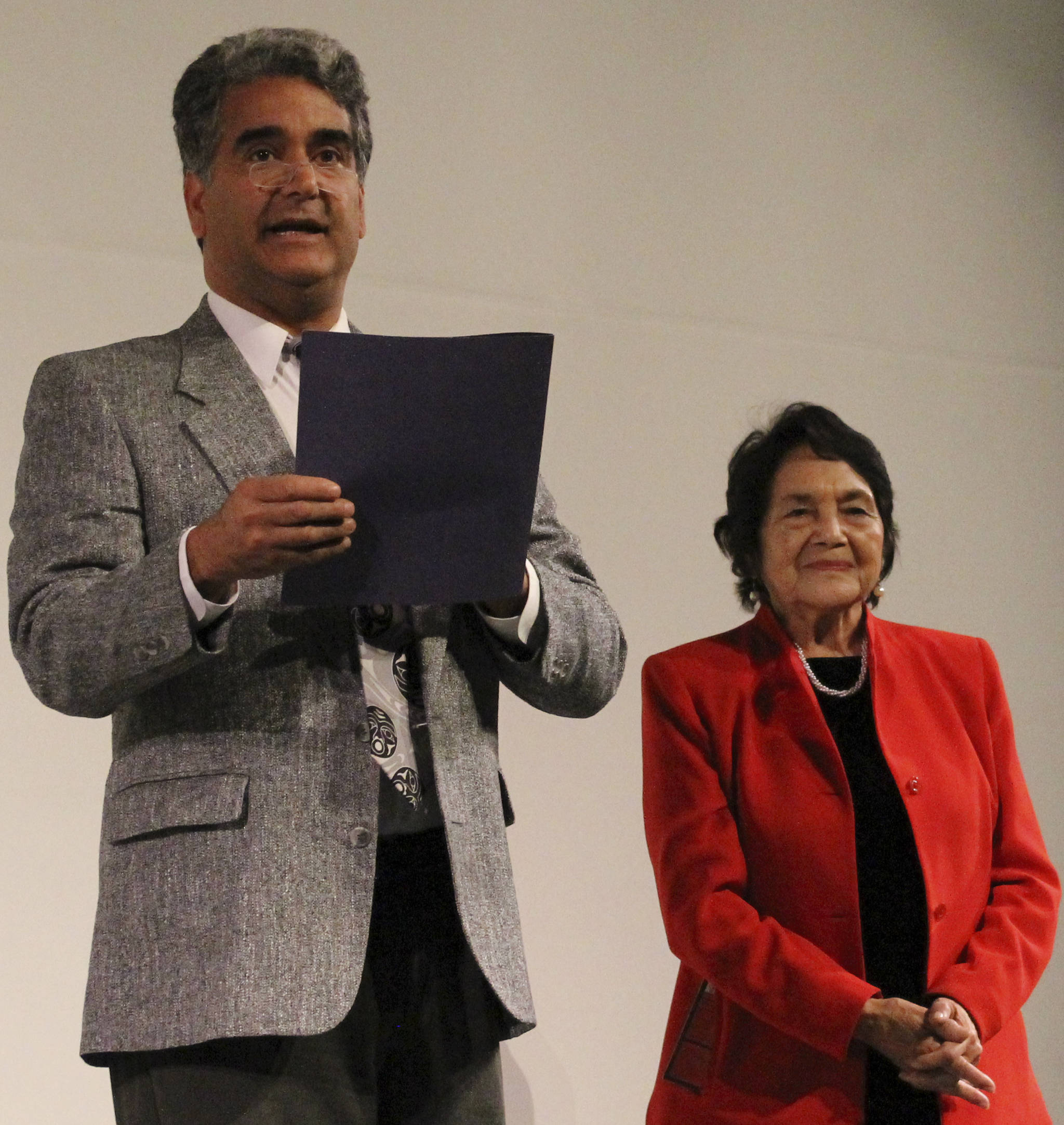

Friday Harbor Mayor Farhad Ghatan thanked Huerta for her work before the screening of the documentary. He also read the town proclamation, declaring Jan. 29 Dolores Huerta Day.

“Whereas the Town of Friday Harbor is a community that celebrates the accomplishments of individuals who work for the advancement and protection of individual rights, and … over the last century Ms. Dolores Huerta has been one of the greatest champions for protecting the civil rights of workers and promoting equality of women … the Town of Friday Harbor wishes to recognize Ms. Huerta for her accomplishments, “ the proclamation states.

Kids from Friday Harbor High School, as well as students from Bow Edison, watched “Dolores” earlier that day. After the film, they watched as the 5-foot, 2-inch, 87-year-old took the stage with a sparkle in her eye. The Whittier Theatre came alive with chants of “Si se puede,” or “Yes, we can,” a phrase Huerta came up with in the 60s, which President Obama later borrowed during his presidential campaign.

“I am so grateful she graciously let me borrow it,” Obama said when presenting her with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2012 at the White House,“because Dolores doesn’t play.”

This award is the highest civilian award in the United States.

Raised in the agricultural region of Sacramento California, Huerta witnessed the hardship farmworkers face. In the early 60s, she was knocking on doors to register people to vote, bringing her up close to their destitution.

“I didn’t understand why, when they worked so hard, they had so little,” Huerta told the Journal, going on to describe dilapidated houses with floors of cardboard, and other signs of extreme poverty she witnessed. She could not stand by and do nothing.

“I had a calling, and I felt it so strongly,” Huerta said.

She teamed up with civil rights activist Cesar Chavez forming the United Farm Workers Union.

In 1965 farm workers went on strike and boycotted grapes grown by non-union companies, as well as the stores selling them. The protest lasted for years, but they eventually secured a union contract, minimum wage and safety protections, including ensuring the workers have water and a bathroom at the work site.

Unfortunately, Huerta told the Journal, the issues facing farmworkers are still similar. Laborers are underpaid and face health issues including cancers and a high rate of birth defects, due to exposure to pesticides. There are few protections on the federal level, let alone the state level.

“You can’t live without food,” said Richard Chavez, brother of Cesar, in the documentary. “Yet, these [agricultural] jobs are the worst paying jobs on the planet.”

Huerta has been arrested 22 times fighting for civil rights and was jailed once for 10 days, for trespassing. But, according to her the scariest moment was when someone attempted to break into her house while she and her children were inside.

“My youngest son always insisted I lock the little chain on the door,” Huerta told the Journal with a smile. “Well, one night, someone knocked at the door. I went to open it, and this man tried to push the door open, break in. Because the chain was latched, I was able to keep him out.”

She continued the story saying she recognized the man later while walking with friends. Her knees buckled, and her companions had to hold her up.

Threats to Huerta came from all angles, not just the police or the agricultural corporations. The Teamsters Union, one of the largest and earliest unions in North America, themselves were belligerent that a woman was speaking out, and accused her of neglecting her children, the film points out.

The movement, “Dolores” explains, was rife with sexism. Huerta’s perspectives changed over the years. She says she originally didn’t care if she received credit for her work, and women often don’t, Huerta says in the documentary. Now, after having men so often take credit for her accomplishments, Huerta advises women, “put your name on it.”

Despite these challenges, Huerta says, there has been plenty to uplift her, including the incredible people, fellow activist leaders and supporters she has met along her journey.

She now sits on the board of Feminist Majority Foundation, an organization dedicated to women’s equality, reproductive health, and non-violence. She has been heavily involved in other social justice issues as well, including gay rights, black lives matter, and Native American rights. The documentary illustrates her work to advocate for all the people, even today.

Currently, some of the causes Huerta is focusing on is registering and urging people to vote, as well as encouraging people to run for elected positions.

“The only way we can make a change is to be in those offices and create the change,” she said.

Education is key, and keeping kids in school is critical as well. African American students are suspended, or expelled at an alarmingly high rate, Huerta said, and often schools call the police without bothering to call the child’s parents. The Dolores Huerta Foundation has been advocating for schools to change their policies and suing those districts if needed.

Huerta also has a plan to take steps in eradicating racism. Her plan begins in the schools, teaching inclusive history. Students are currently not taught how Native Americans were treated as European settlers arrived, Huerta said, that it was African slaves who built the White House, the walls of Congress, even Thomas Jefferson’s home in Virginia, or that immigrants from across the world were brought here to build, she explained. The result is that children of color feel disrespected, while white children are fed the idea they are superior.

“We have to start teaching our children so we can stop this crazy racism,” Huerta said.

There has been slow progress, Huerta said, noting some school districts the foundation has worked with have changed textbooks to reflect a more thorough, and factual history, but there is a long way to go.

“We have to come together, we have to become active, and we will come out stronger and better,” Huerta said in closing remarks to the community theater attendees.

“Si, se puede,” the crowd chanted.

“Dolores” will be aired on PBS, March 22.

For more information on the Dolores Huerta Foundation visit their website at doloreshuerta.org.