Treaty tribal and state co-managers wrapped up their annual process of setting salmon fishing seasons recently and I was again reminded of those who say that a total ban on fishing is the only path to salmon recovery.

They don’t truly mean a total ban though, just one on Indian and non-Indian harvesters. They don’t want to talk about all of the fish lost to dams, poisoned stormwater runoff and low stream flows. Those environmental factors “harvest” salmon just like any fishery. A dead fish is a dead fish no matter how it dies.

The tribes and state manage salmon harvest on the knife’s edge, developing limited fishing opportunities that target healthy, mostly hatchery raised fish. Because most wild stocks are too weak to support harvest, without the salmon that tribal and state hatcheries produce there would be no fishing at all in western Washington.

The combined state, tribal and federal hatchery system in western Washington is science driven and finely tuned to produce enough fish for harvest. Most of these hatcheries were built to make up for lost habitat. Those hatchery fish provide meaningful harvests to many, but they can also hide the true health of the habitat in our watersheds.

While the total number of chinook returning to Puget Sound has remained steady for the past decade at about 200,000, the percentage of wild fish in that figure has been shrinking. It tells me that we are holding the line on harvest, but we are losing the fight on habitat. We are putting tighter and tighter controls on how we fish, but each year we lose more and more natural productivity from the little good habitat we have left.

All of the fishing cutbacks, changes in hatchery operations and habitat restoration work of the past 20 or 30 years can’t begin to make up for the centuries that this region’s environment has been assaulted. Habitat loss and damage alone are driving the decline of wild salmon. We are at the end of an era and we have no choice but to change if the salmon are going to survive.

The treaty tribes have a higher standard for salmon recovery than the Endangered Species Act. For us, salmon recovery means restoring all salmon stocks to populations that can support sustainable harvest. It’s about continuing to be who we’ve always been: fishermen.

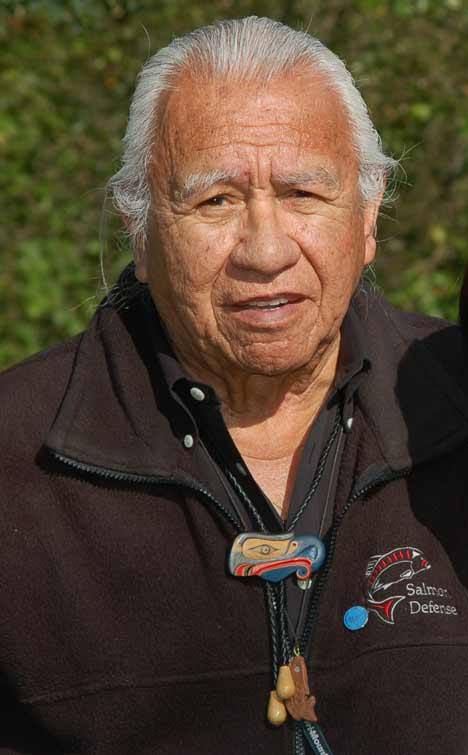

— Billy Frank Jr., Nisqually, is chairman of the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission. Commission members with ties to the San Juan Islands include the Lummi Indian Nation, Swinomish Indian Tribal Community, and the Tulalip Tribes.