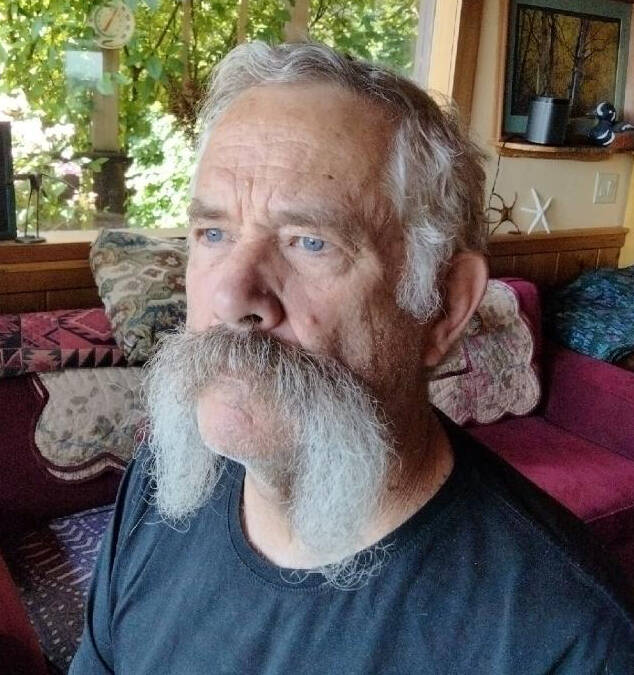

By Steve Ulvi

Journal contributor

My desk of inspiration fronts a large window facing northeast; nearby madrones and conifers giving way to a viewshed of sunrise, ridges of many other islands intermittently sun-splashed or enclouded, bone white moon rise and Mt. Baker. A recent winter morning dawned in cloud-hidden silence at our forested place on Mt. Dallas. The seclusion of dense fog is calming, even pleasing, in the way of a Sung Dynasty Chinese landscape painting.

The first guttural calls seem to come from nowhere, yet everywhere, announcing our local clan of ravens launching into the grey mist from their towering roost tree near the house. The lustrous blackbirds begin their food search with varied calls as they course toward the farmlands below. Other mornings invite play as gusty winds or updrafts lift them skyward. Heckling barrel rolls are common, almost unknown among other birds, and seemingly without practical purpose. Varied calls, difficult to mimic, remind me of their omnipresence; way out they climb in spirals with swishing, pumping wing beats like swimming in air, then soar with eagles or tilting vultures, their calls carrying a very long way. Stealth is hardly the raven’s way.

My life has been enriched by common ravens for over six decades in all seasons across the mountain west – from the colored cliffs of New Mexico and Arizona north to the treeless north slope of Alaska- their aerial mastery, creative vocalizations, curiosity, learned behaviors and a gritty ability to survive extreme conditions never fail to spark my interest. Highly adaptable, common ravens succeed from desert to tundra biomes on every continent but Antarctica making them one of the most ubiquitous, and noticeable creatures on earth. They are even seen high in the whiteness of the Denali massif scrounging climbing camps in thin, oxygen-depleted air far above natural habitat.

Ravens naturally live in small, dispersed family groups in wild country but landfills and human excess attract them from far and wide, especially during winter, and to my mind those habituations diminish their essential character. Large flocks of ravens raiding dumpsters, teasing chained dogs, stealing golf balls or windshield wipers, and spatter-fouling unsecured pickup loads in Fairbanks do not impress like small clans flourishing in the wild reaches of Alaska. Everywhere you go, no matter how far into the unpeopled landscapes, they soon appear, out of curiosity and snooping for nutritional reward.

I consider them to be amongst my favorite creatures. Their complete blackness is something of an evolutionary mystery. I have seen two grey ravens in nature but never an albino bird. They have alerted me during subsistence hunts, especially for caribou in folded tundra uplands on several occasions. I always reward them, in the field and at home with butchering offal or fish waste as a measure of my abiding respect. Their exuberant lives refresh me daily and help to keep me grounded in the natural world, especially here, where we live with such a diminished assortment of land-based creatures.