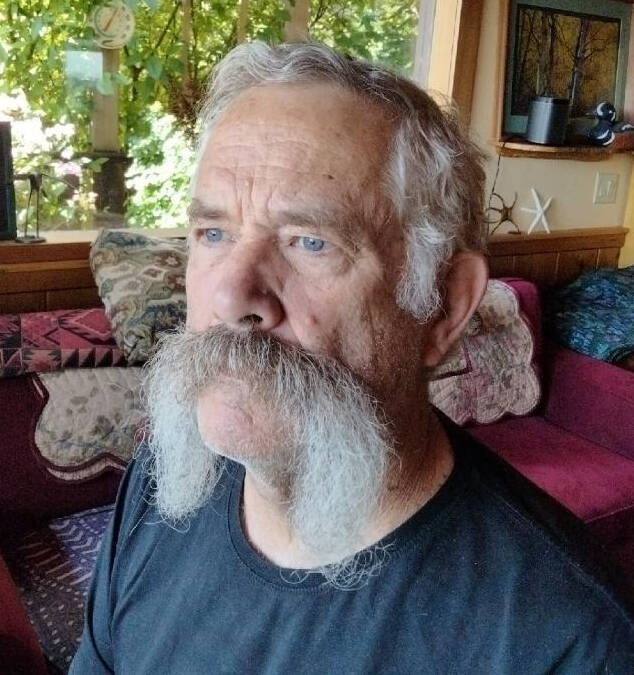

By Steve Ulvi

Journal contributor

This story comes from Alaska, some 2000 miles north as the Sandhill Cranes fly, entering the maw of another subarctic winter. So distant from the maritime abundance and ease of this island.

Life in the Alaska bush in 1980 was as gritty and challenging as ever while the radio buzzed with political anxiety and fear-mongering about “the end of traditional lifeways” in bush Alaska. In mid-December, the Alaska Lands Act would establish huge, non-traditional parks and refuges that attracted me into a crucible of inspiration and upheaval.

In the brief days of mid-November, ice shelves built from shore as metastasizing pans spun in the sluggish, misting current with a crystalline grinding. A heatless sun had slipped below the southerly ridge not to reappear until mid-February. The transforming river, a half mile wide, was dangerous to cross for up to seven weeks, leading to family isolation until accumulating snow and freeze-up prepared the immense boreal landscape for winter travel.

Barren hardwood branches clacked like a million chopsticks as the temperature rose and freshening wind from a welcome snowstorm swept what we called Windy Corner. Nearby, the longitude-straight swath of the Canadian-US border crossed the river valley where high ridges constrained and accelerated surface winds. Our small hand-tooled cabin hunkered under a canopy of spruce on the north bank about 10 miles from the village and town that each clung to the opposite bank. No neighbors.

For hardy northerners, the holiday season was a troika of celebration – Thanksgiving, Winter Solstice and Christmas – with daylight diminished to under 5 hours, the mercury sometimes falling to 30 below. The New Year would spawn truly frigid temperatures. A headlamp was essential to extend outdoor time for mushing dogs, hauling wood and water, cutting trail, snowshoeing, town trips and setting out traplines. The landscape shone bone-white with subtle grey-blue shadows, under big moons and dancing auroral lights. Indoors, kerosene lamps burned for many hours.

As Thanksgiving morn dawned at 9:30, the temperature rose to -5F. I jacketed to water the frisky, staked dogs and strode rifle in hand to the high riverbank to scan the river. A few members of the local raven clan swooped overhead, chortling in recognition. The far ridge was obscured, dry flakes swirled to pepper my face. Maybe a week to freeze-up. I turned past the garden where a grizzly had dug up buried salmon offal weeks earlier. We prayed that beast was in the mountains behind, hibernating.

Lynette and the kids intercepted me, puffed in homemade clothes and moosehide boots, grinning proudly, cheeks flushed. Three more snowshoe hares from the woodlot snares! A rare moose-less fall, but canned black bear, last of the potatoes, pickled veggies, salmon strips, hare and lynx hindquarters fried in sweet bear fat would do. Fresh cookies with powdered milk yogurt would make it special.

During bedtime stories, the dogs took to sonorous howling, bellies full of dry chum salmon, then curled nose-under-tail on spruce boughs, the falling snow building on thick fur for another long night.