At its most complex, Matthew Gray Palmer’s latest sculpture, “All Things within All Things” incorporates sophisticated themes of connectivity.

At its most basic, it is just really, really cool.

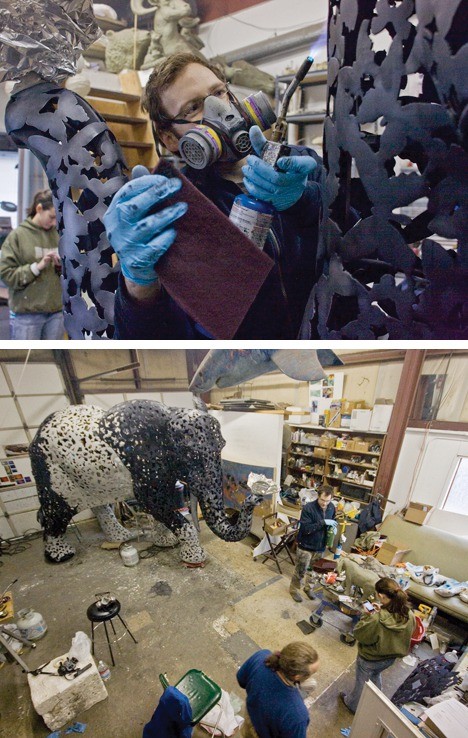

This seemed to be the consensus among those who flocked to the open house on Jan. 3 at Palmer’s Friday Harbor studio. Standing at a little less than 10 feet, the aluminum creation drew the full gamut of amazed exclamations from people. Because if nothing else, it is unusual to see a life-sized African elephant crammed into an art studio. Palmer, however, was convinced it would get out of the door.

The self-taught sculptor seemed calm in the face of his (literally) elephantine achievement. Although such composure may be due to an inner calm, the long and late hours needed to complete the project probably contributed. In the two months that marked the final stages of construction, Palmer’s hours have gone from “super long” to “ridiculously long.” To see the piece is to understand why.

Although the structure is realistic in shape and proportion, it is composed entirely of butterfly silhouettes. For the viewer it presents an impressive feat of craftsmanship, and for Palmer it marks a step towards the conceptual and away from the representational: “This project was more akin to some of my more personal work for galleries or spec,” he said.

So far, his public works have tended toward realistic reproduction of form. Many Palmer pieces occupy places in national parks. The work is both a blessing and a limitation; model sculpting provides him with a living, but it also confines him to a niche. Palmer hopes that the more abstract aspect to his elephant will open doors to more stylistic avenues of work.

Palmer certainly worked hard enough to open those doors. It has been two years since he won the contract, besting 50 other artists, and a large portion of that time went to the paperwork. “Matthew has had big contracts before,” said his wife, artist Danielle Dean Palmer, “but this one was about 40 pages long.” Additionally, the City of Norfolk, Va., whose zoo the sculpture was intended for, had initiated a new public art program with Palmer as its first artist. Matthew said this contributed to the red tape and paperwork.

Not to mention the hours commanded by the elephant itself. The shapes were formed by hand and a plasma cutter. Artist Micajah Bienvenu lent assistance and let Palmer use his studio and technology to do the larger portion of construction before the piece was moved to Palmer’s studio for finish work. Palmer is attentive in mentioning his thanks to all those in the community who helped him in last stages. Artist Tom Small, for example, went to the studio the day after the open house, donned a respirator and helped Palmer and his wife apply the wax finish. Several friends and patrons brought food and coffee to help Palmer through the final stretch. The sculpture’s incomplete state at the viewing may not have bothered the public (Palmer said people enjoyed seeing a “work in progress”), but it did not change the fact that with 24 hours to go, a portion of the body remained unfinished.

“Unfortunately, it is always that way,” Palmer said of how fast time ran out. “I always think, here we are at the end again.” Danielle agreed, recalling a previous incident where she drove a shipment of models to SeaTac Airport with an exhausted Palmer still painting a piece in the back.

Fatigue, however, did not stop the elephant from being loaded up and shipped out on the allotted date. A few days later, before he was due to fly to Virginia for the installation, Palmer mused about the success of the piece. “I’m too close to it right now, ask me in six months,” he said. It is not hard, however, to gather what the rest of the world thought of “All Things within All Things.”

“On the mainland we were chased, we had people honking at us and giving us the thumbs up, even in the ferry line,” Palmer said.

To Palmer, the piece may be complex and personal, but to the outside world it remains simply really, really cool.