Called “the jewel of winter” by an attendee, the revered Arthur Whiteley Lecture Series at the Friday Harbor Labs this year is full of sharks, biomimicry and deep ocean exploration.

The series, hosted by San Juan Nature Institute, is named after Arthur H. Whiteley, a devoted professor of zoology at the University of Washington and researcher at the labs who passed away in 2013.

The lectures are open to the public and take place at 7 p.m in The Commons, at UW Friday Harbor Labs.

“He knew everyone at the university, he always kept an eye on what papers were being published and who was at the forefront of their fields,” said Fiona Norris, executive director at the institute.

Norris, a retired botanist originally from South Africa, has worked with the nature institute for 12 years, and said that the lecture series has gone on for at least a decade, attended by students, researchers and islanders.

“If they’re curious, this is the best place to exercise those curiosities,” Norris said. “We can’t all go out on those ships!”

Finding human uses in nature

The series was kicked off Jan. 21 with a presentation on biomimetics by Adam Summers, resident scientist at Friday Harbor Labs. Summers, who has been at the labs since he was a graduate student in 1991 discussed how his background as a natural historian and engineer led him to studies in biomimicry, a category of research that looks at how humans can imitate natural structures, processes and patterns to create new products or methods that can be beneficial to humans.

Some examples Summers gave were the superior filtration methods of manta rays in Hawaii, studying the strength and longevity of different shark teeth, and the Northern clingfish’s suction abilities, which was reported on by the Journal in the Jan. 6 edition.

“We’re all blue sky researchers looking at problems that look like they’ll never have solutions,” Summers said, referring to “blue sky research” that focuses on the curiosity behind the hypothesis, rather then research with an agenda. Summers’ research often looks at a part of an animal and asks “why? how?” and then may find applications afterwards. In the case of the manta rays, who are filter feeders that eat plankton, researchers found the manta’s natural filtration system to be superior, and tried to emulate it with a bioinspired, nonclogging filter.

In the case of the shark teeth, they created saws made out of shark teeth to recreate a shark feeding by cutting through 60 pounds of chum salmon. They found the teeth dulled remarkably quickly, different shark species teeth were better at cutting through different prey, and that explains why they replace their teeth so often.

Protecting coastlines without armoring

Megan Dethier is the third lecturer, a research professor in the biology department at the University of Washington and full-time resident at the Friday Harbor Labs.

For the last six years, Dethier has been doing research around the Puget Sound to answer this question: What are the ecological and geological ramifications of taking down or putting up shoreline armoring?

Dethier’s talk, “Armoring on shorelines: Documented impacts and implications for future actions” focuses on the practice of armoring, a technique that uses physical structures like bulkheads, seawalls and cement to hold erosion at bay.

While the immediate result is stabilized shorelines and houses safe from erosion, unintended consequences include changes in sediment deposition, reduction in the quality of marine habitat and disruption of natural cycles. Dethier said armoring isn’t all bad or all good, but rather about finding a balance and looking at other options like “green shorelines” that use vegetation and organic composition to stabilize shorelines.

According to Dethier, armoring is not often used on the San Juan Islands because the solid bedrock gives enough strength against erosion. But, Dethier, said, it’s important for people to know the impacts armoring can have in case they are thinking about installing it, or looking to remove preexisting armoring.

Because her research involved requesting permission from landowners to look at armoring on their private property, Dethier said she experienced a wide range of reactions, from welcoming them with coffee and cookies to an armed landowner who demanded they leave immediately.

“It’s a hard topic to talk about because it’s so political,” Dethier said. “But it’s a science project so that’s what I’m going to focus on, and being objective about it.”

Dethier’s talk will be the on Feb. 25 at 7 p.m.

A world yet to be explored

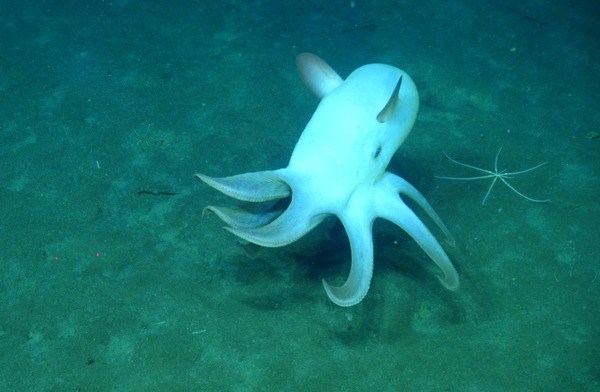

The second lecture in the series, “Modern Voyages of Exploration” takes the audience deep diving with remote operated vehicles to witness a world that’s barely been explored.

According to the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration, just 5 percent of the world’s oceans have been explored.

Spring Street International math and science teacher Tim Dwyer will share his experience as a 2015 Science Communication Fellow aboard the Exploration Vessel Nautilus, with Titanic discoverer Richard Ballard.

At the core of his lecture is Ocean Networks Canada, which operates cabled observatories, or oceanographic research platforms that rest on the seafloor. The cables are a continuous data collector reading oxygen levels, salinity, facilitating forensic studies, and audio research and more.

They pull in 170 gigabytes of data per day from the 850 kilometers of cables off the coast of Vancouver, in Saanich Inlet and the Strait of Georgia.

Using the cables instead of ships allows for larger quantities of data, is ultimately cheaper then running a research ship, and lowers human risk. The new

technology, Dwyer says, allows for a whole new frontier in exploring the ocean.

“We live in an extraordinarily diverse marine and geologic part of the world,” Dwyer said. “There’s a lot we don’t see all around us. It’s a really fascinating time to get into oceanography.”

Dwyer will be speaking Jan 4 at 7 p.m.

Stories of sharks

By the time Helfman was 13, he had read almost every book ever published about sharks.

“I never grew out of that fascination,” he said.

Helfman is a Lopez Island resident and the author of “Sharks: The Animal Answer Guide.” On March 30, 7 p.m. he will present 25 things you did not know about sharks at 7 p.m. in The Commons.

Helfman hopes his talk will help people have a greater appreciation for the diversity of species and behaviors of the 500-plus shark species, and not just the half dozen that most people are aware of.

“Sharks are amazing animals — they give birth to live young, some are warm-blooded, some frequent fresh water, some live to over 100 years, and much more. Many are endangered,” said Helfman. “They deserve more than fear.”

After his boyhood love for the fish, Helfman landed a dream destination of The Republic of Palau when he applied for the U.S. Peace Corps. Palau, also called “the underwater Serengeti” offered a wealth of marine study including leopard, white tip reef and grey reef sharks. Later he studied sharks off the coast of California. For his doctorate he took on fresh water fish as his topic of research always devoting time to lecture of sharks specifically.

Through his years of lecturing he honed his skills as a public speaker byfocusing on the audience.

“Every audience deserves to be treated as if it’s the most important group you’ve ever spoken to. If folks are willing to give up an evening to listen to me, they deserve to be both enlightened and entertained,” he said.

When he retired he finally sat down to write a book about his favorite sea creature.

He started writing with a small audience in mind – boys ages nine to 15 but as he came closer to finishing the project he found that boys, girls and adults at any age were also interested in sharks.

His favorite shark is the endangered basking shark because they are gentle giants and little is known about their habits including their reproductive biology, how long they live and where they go most of the year.

The shark’s decline started in the 1990s because high numbers were getting caught in fishing nets and the Canadian government authorized ramming to keep them from being a nuisance.

“They’re endangered because we’ve mistreated them for no reason other than they were a nuisance,” said Helfman. “They’re no longer hunted but are very slow to recover, which is common among sharks. I’d love to see one in the wild (none have ever been kept in captivity).”

To read more about the basking shark, visit ww.sanjuanjournal.com and search “shark.”

– Editor Cali Bagby contributed to this article.