The summer of 2025 has been one of the San Juan Island’s Museum of Art’s busiest summers since pre-COVID, according to Director Blake DeYoung, and the response to the current exhibit “Shapeshifters,” running through Sept. 15, has been overwhelmingly positive.

“Several people have been moved to tears. Many stay for a very long visit, or come back for a second or third visit,” DeYoung said.

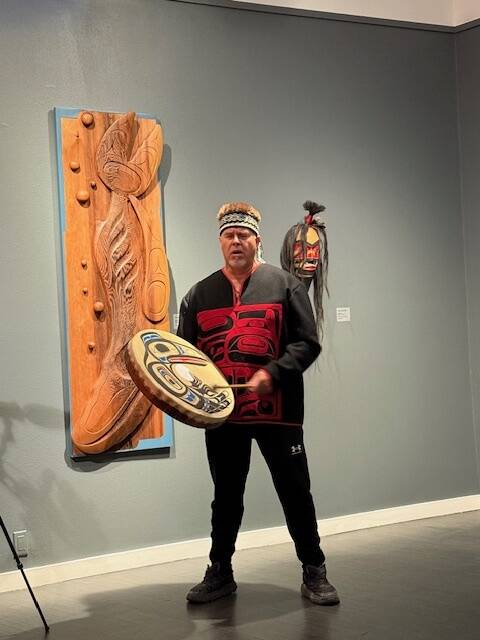

The exhibit, guest curated by Lee Brooks, showcases the extraordinary diversity of contemporary Indigenous Northwest Coast Art. Works featured include luminous glass, bronze sculpture, red and yellow cedar carvings, basketry, serigraphs, argillite and multimedia art by some of the Northwest’s most renowned Indigenous artists.

The main gallery is divided into four sections representing four of the unique Native cultural styles of the Pacific Northwest. Works by Susan A. Point, Musqueam, representing the Coast Salish/South Coast culture. Rande Cook’s work represents the Mid-Coast/Kwakwaka’wakw style; Christian White’s art represents the Northern-style art of the Haida, and Tim Paul’s Nu-Cha-Nulth/West Coast style work completes the main gallery display. Works by Native luminaries, such as Richard Hunt, Reg Davidson, Greg Colfax, Gordon Dick and Dan Friday are also represented.

Due to current politics, there were challenges bringing both art and artists across the Canadian border to Friday Harbor. There were pieces the Museum intended to include that they could not get across the border, for example, and artists who planned to speak over the summer yet declined to travel under the circumstances.

“Lee Brooks was essential,” DeYoung said. “As the US and Canada navigated new policies around tariffs and the exchange of goods, it became obvious that this was going to have an impact on both art and travel. SJIMA has brought international work to the museum before, but the dynamics of last spring created a lot of uncertainty, even among professional trade brokers.”

DeYoung also gave a shout-out to SJIMA Assistant Director Wendy Smith for an amazing job designing the show in a way that lets visitors get close to the work and connect to what the artist is saying – she managed to remove the physical and emotional barriers and bring the art closer to the soul.

He continued, adding, “What ultimately did solve most of the problems, however, was Lee’s deep connection and strong relationships with these artists. It was a great reminder that, no matter what volatility and conflict occur between governments, there are human beings in both locations who desire to connect and share their lives with one another.”

Cook also credits Brooks, saying in the SJIMA artist profile video that Brooks, seeing the fresh look of his work, a mix of modern and traditional style, was the first gallery owner to offer him a show.

The four artist profile videos, produced by Roy Cox, have also deepened attendees’ understanding and appreciation of the exhibition. The interviewers in the videos are Docent Coordinator Marney Reynolds andSmith, and participating artists are Cook, Friday, White and Dick. They can be found on SJIMA’s website at https://www.sjima.org

Each of them discusses being involved in the arts at a young age.

“I was always an artist, I think I’ve always felt I had it in me,” Cook says, describing sitting around the kitchen table with his grandfather, drawing. His grandfather was an accomplished artist in his own, and taught Cook traditional styles, though not at first. For many years, he would tell Cook to “go over there and draw that.”

“What that did was open me up,” Cook said, enabling him to see things from both a modern and traditional point of view. The shape of the object, he continues, is drawn first, and then the indigenous elements are added.

Cook also explains that he never crosses the boundary between commercial and ceremonial. The stories they have, the ceremonial objects are sacred, he adds, and not for sale. Through his commercial art, however, he explains he wishes to create work that resonates across boundaries, cultures, and ethnicities. “It isn’t about race, it’s about who we are, celebrating life, the essence of life,’ Cook says in the interview. “And we can’t do that without a healthy planet.”

Dick also reflects on time spent with his grandfather during his childhood, and how childhood memories in general play a large role in his art.

“I’m always very thankful for my upbringing,” he says.

Dick also mentions his reverence for the natural world, explaining one of the reasons why he doesn’t use a lot of paint, if any, in his carvings is because the wood itself is already so beautiful, and “I don’t want to compete with nature.”

White was born and raised in Haida Gwaii and is known in part for his bentwood boxes. For those unfamiliar with the boxes, they were used for everything from cooking to funeral boxes, storage and travel. White explained there is an expression from birth to burial, “the boxes were used for everything.”

The designs on the boxes were universal, White says; however, each artist develops their own style. White is also known for his pole carvings, and in 2022 carved one of the largest totem poles in Haida Gwaii. Totems, he explains in the video, are like crests, “I like to tell the stories about how we got those crests,” White said.

Serendipitously, “Shapeshifting” led to else – as SJIMA opened the show, the staff and board welcomed two artists to be a part of the launch: Christian White of the Haida in British Columbia, and Dan White of the Lummi Nation. “We had no idea that the Haida and Lummi had planned a healing and reconciliation gathering on Orcas for the following week to resolve conflict going back generations. As members of each group came to San Juan County that weekend.” DeYoung said, adding that SJIMA served as a gathering place where they could meet and prepare themselves for that ceremony. “It was a deep honor that the museum was a visual illustration, through both art and people, of this reconciliation.”

When asked about the importance of the exhibit, DeYoung said, “On both a practical level and a spiritual level, there is so much interest in understanding and honoring the people and cultures that were here long before the rest of us. We really tried to get out of the way and let the work and artists speak for themselves.”