By Darrell Kirk

Staff reporter

When OPALCO purchased 20 acres of forested land on Decatur Island in March 2025, many residents expressed concern. The proposed expansion of the island’s existing solar array—clearing approximately 8 acres of second-growth forest for up to 2.1 megawatts of capacity—has united the fractured community in opposition and exposed tensions about how San Juan County will meet its growing energy needs.

The conflict on this island of 142 registered voters raises questions far beyond its shores: Where should renewable energy infrastructure go? Who decides? And how much is any one community expected to sacrifice for the greater good?

Why Decatur?

The answer lies partly in decisions made decades ago.

“Decatur is zoned Rural General Use, which allows commercial energy production with a conditional use permit,” explained Justin Paulsen, a San Juan County Councilperson. “Most of San Juan County is zoned Rural Farm and Forest, which doesn’t allow commercial energy production currently.”

That technical distinction severely limits OPALCO’s options under county code written 20 to 30 years ago for “big diesel generators,” not solar arrays.

“Times have changed, life has changed, technology has changed,” Paulsen said. “Our code has not.”

But there’s another critical reason: Decatur sits at the heart of San Juan County’s power grid.

“The power that feeds San Juan County runs from Anacortes through the middle of Decatur and then feeds to Lopez,” Paulsen explained. “If you cut the line between Decatur and Anacortes, San Juan County loses power.”

This infrastructure reality—the power line predates zoning—explains why OPALCO views Decatur as a logical expansion site.

“Decatur was selected due to its proximity to the existing solar site and substation,” said Krista Bouchey, OPALCO’s Manager of Communications. “Expanding existing facilities is more efficient and generally less impactful than building entirely new infrastructure elsewhere.”

Behind the project lies a regional energy crisis. “The hydropower systems that have historically supplied most of the Pacific Northwest’s electricity are at capacity, coal plants are being shut down and natural gas generation comes with a carbon-based financial penalty,” Bouchey explained. “Given our remote location, our best bet for clean and affordable firm power is to build renewable generation projects locally.”

The two submarine cables serving San Juan County are aging and at capacity. OPALCO says the project would generate approximately 2,275 MWh annually—about 1% of the cooperative’s total load—while utilizing a $1 million state grant to support low-income energy assistance programs.

Community Opposition

Many residents remain unconvinced by OPALCO’s rationale. While supporters of the project exist on the island, most vocal residents oppose the expansion. Several residents who support or have mixed feelings about the project declined to speak on record, with some citing concerns about community backlash in what has become a divisive issue.

Bill Hurley, a Decatur Island resident and marine engineer, captured widespread concerns:

“The temperature on the island is very hot. All who are speaking out on the proposed array are against it at the proposed site, and many against it on the island at all. There may be people on the island who are in favor of the installation, but we are not hearing from them.”

Hurley framed his opposition around three points: “I want solar and renewable energy but it needs to be promulgated correctly, and if it doesn’t make sense for a specific site it should not be installed because it sounds like the right thing to do. The proposed Decatur array is not right.”

His framework—Wrong Site, Wrong Island, Wrong Plan—has become a rallying cry for opponents.

“Wrong Site: It involves 8 acres; deforestation and destruction of the current healthy ecosystem,” he wrote. “Wrong Island: There is only one ramp to accommodate all roll-on roll-off vehicles and equipment. Decatur is not a ferry-served island, hence access is expensive and limited. Decatur does not have a fire district. There are no paved roads or infrastructure to support the installation activities. Wrong Plan: I have heard all the arguments from our power company on why this is needed, why it is critical, and I can’t make sense of it. Each of their arguments can be questioned and countered. It does not add up.”

Despite his opposition, Hurley emphasized his commitment to working within the system: “I am willing to fight against it in a respectable manner, working to the full extent within the system to help get the system to realize that this is just not right. Good intentions, bad execution. Right idea, wrong site selection.”

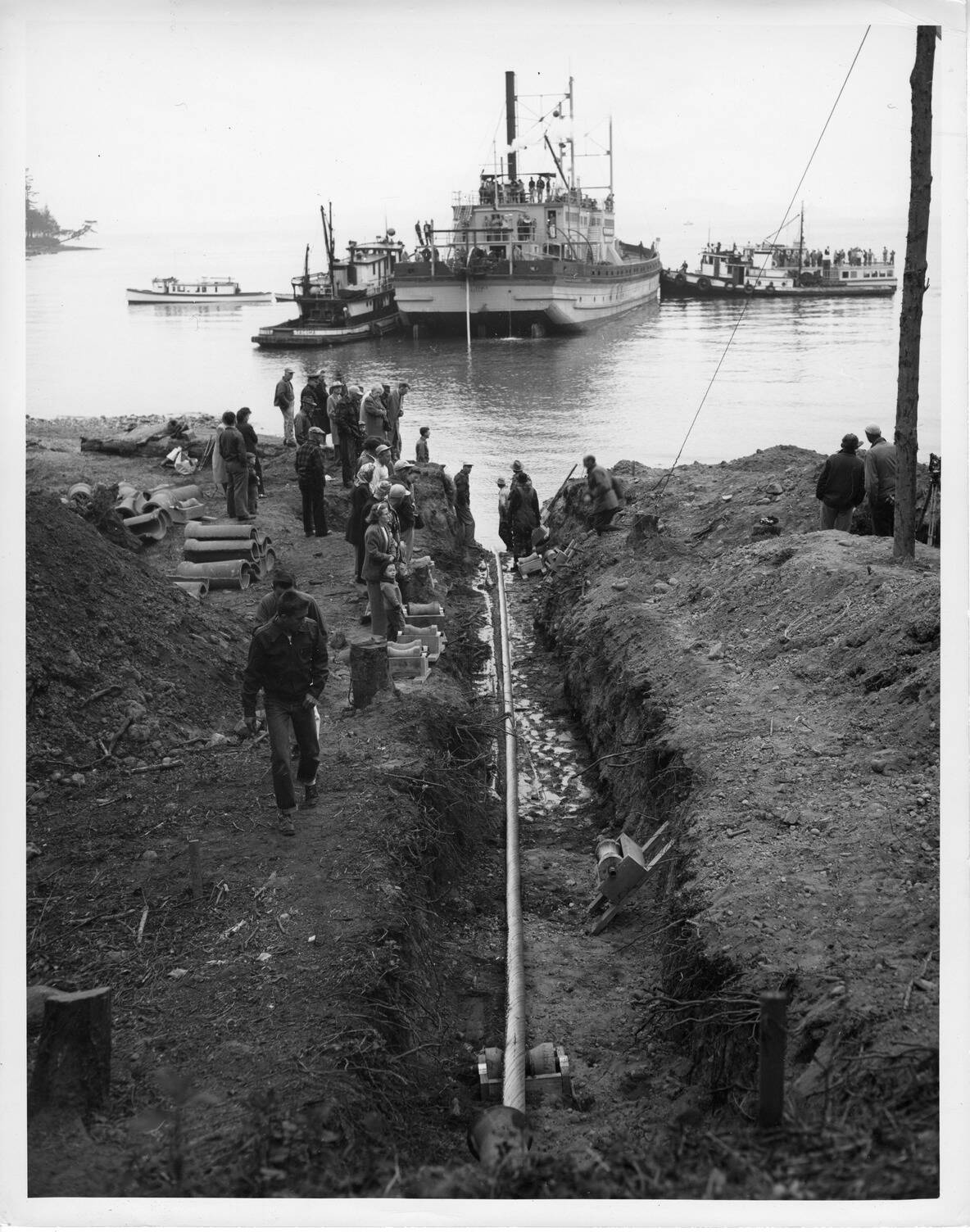

Kendra Lamb, whose family has lived on Decatur since 1870 and whose father helped lay the power cables that supply electricity to the island, disagrees with OPALCO’s site selection.

“I feel that the microgrid we have is our equitable share. Why were we given the first turn? And as our reward, we are being given the second turn,” she said. “We are a small non-ferry serviced island with no fire district and one county ramp. We weren’t chosen on our appropriateness. We were chosen because we were considered the path of least resistance.”

The Baylor Hill Question

Nothing fuels residents’ concerns more than OPALCO’s Baylor Hill project on San Juan Island. After four years of planning, the project stalled amid permitting issues. When OPALCO pivoted to Decatur, residents noted San Juan Island’s project had stalled.

“I cannot believe that after OPALCO failed to gain approval for the Baylor Hill site—an open field with sheep grazing beneath the panels—they would now be permitted to clear a second-growth forest,” said Dawni Cunnington, a 25-year Decatur resident.

Bouchey pushes back: “This is not true to state that public opinion stopped the Baylor Hill project.” The delays resulted from county permitting requirements, making the timeline “unfeasible.” OPALCO still owns the land and “hopes to pick this project up again in 2027 at the earliest.”

Paulsen confirmed: “I expect them to bring that project back and make it happen.”

He emphasized more solar is coming everywhere. “More needs to be done on Orcas, more needs to be done on San Juan, more needs to be done on Lopez,” he said. “OPALCO just happens to own property on Decatur to do it.”

But for residents hosting the county’s only utility-scale solar array—one of just two in Western Washington—many remain unconvinced.

“We already took the first turn,” Lamb said. “Somebody else needs to take a turn.”

Paulsen stressed every island will face similar decisions. “This conversation needs to happen on every island and is going to happen on every island,” he said. “Decatur is just the first of many examples.”

Fire: The Flash Point

Fire safety dominates resident concerns. Decatur has no fire district, no paved roads, only a volunteer brigade. The island has experienced two major fires.

Charlie Conway, a 16-year part-time resident transitioning to full-time, highlighted fire concerns that OPALCO “has so far failed to address.”

“The proposal entails significant risks of wildfire and stormwater runoff,” Conway said, noting that fire response capabilities are severely limited on an island without a fire district.

OPALCO offers a different assessment.

“This solar site has a very low probability of causing a fire,” Bouchey said. “The panels are rated to not contribute to a fire that can be sustained by grass and vegetation under panels.”

OPALCO argues the project could reduce fire risk: “The current forest is quite dense with thick underbrush and cleaning up the forest could help mitigate wildfire spread,” Bouchey said, noting fire detection systems and agency briefings are in place.

Environmental Concerns

The site contains nine wetlands. Kim Ferree noted her home sits “at the bottom of the hill where the water runoff will be.”

Both federal and state environmental reviews found the project compliant. “San Juan County has determined that this project does not have a probable significant adverse impact on the environment,” according to the SEPA determination.

OPALCO says only 8.5 acres of the 19-acre parcel will be cleared, with wetlands protected.

But Alan Mizuta has raised concerns about overlooked deed restrictions, including an open space designation from 2012 and a Native Growth Covenant covering 3.82 acres.

Residents and OPALCO describe the forest differently. Residents see a healthy ecosystem. OPALCO notes the forest “has been logged several times,” with “many trees still young or moderate in size” and “signs of tree root disease.”

Communication Challenges

Residents point to broken promises from the first solar array, including landscaping and maintenance failures causing runoff issues.

“OPALCO management has chosen to disregard every substantive mitigation suggested,” said Charlie Conway.

In a letter to OPALCO, Rob Grant, a Decatur resident who invested in the island’s existing solar array, expressed a sentiment shared by many—support for solar energy, but strong opposition to this particular project:

“What you are proposing is paving a large portion of our Paradise for solar panels that won’t return the investment you seek. You are destroying the environment here, and along with it the charm of a central core of our small island. This is unacceptable to us! I am actually a proponent of solar and alternative power generation. I invested in the existing array.”

OPALCO maintains the project is necessary to meet regional power demands. “From both a financial and environmental standpoint, expanding existing facilities is more efficient and generally less impactful than building entirely new infrastructure elsewhere,” Bouchey said.

Grant concluded his letter by quoting Dr. Seuss’s The Lorax: “I am the Lorax. I speak for the trees, which you seem to be chopping as fast as you please! I speak for the trees, for the trees have no tongues. And I am asking you, sir, at the top of my lungs. Oh please do not cut down yet another one!”

OPALCO acknowledges communication challenges, admitting it lacked a complete resident contact list before the property purchase. The May 2025 town hall drew 60 people in person and 25 online.

“We have since rectified our contact list and have held an in-person meeting that was also offered virtually,” Bouchey said.

The relationship remains adversarial, though OPALCO emphasizes its cooperative principles: “We are not asking Decatur to shoulder more of this burden.”

The Broader Dilemma

Even opponents acknowledge the dilemma. Charlie Conway, a 16-year part-time resident transitioning to full-time, articulated the tension many feel:

“Although I believe the threat of global climate change makes it imperative that we move away from fossil fuels, I am opposed to the expansion of the existing solar array on Decatur Island because of the significant environmental and social costs associated with this particular site. Developing the solar array here means clear cutting forest lands and fundamentally changing the character of the Decatur uplands that the Decatur Island community has taken great care to preserve.”

Paulsen stressed that energy decisions are coming for all islands. “A large portion of our population supports this and would like to see it done faster and on a larger scale,” he said. “The projects are going to happen where the opportunities present themselves.”

An Indigenous Perspective

For some residents, the opposition carries deeper cultural and spiritual significance. Tacee Webb’s family descended from Tlingit Chief Shakes’ daughter and Chief Seattle’s lineage, arriving on Decatur Island in the 1860s. Her great-uncle Henry Cayou co-founded OPALCO and served as San Juan County Commissioner and state representative.

The irony is not lost on Webb: her ancestor helped build OPALCO to bring power to all the islands, yet his descendants now oppose what the cooperative sees as necessary expansion.

“In Tlingit culture, there’s a belief that a spirit lives in everything. That spirit is called the Yéik,” Webb explained. “Throughout Haida culture and coastal Salish culture, the words and names are different, but the core idea is very similar. This cultural belief is really like a faith to local tribes, and it’s very near and dear to my heart. So when you tell me you’re cutting down a forest to possibly generate some energy from the sun, it sounds like a sin.”

Henry Cayou helped establish OPALCO in 1937 to serve the broader San Juan County community—a regional mission that now conflicts with what some of his descendants see as environmental harm to Decatur specifically.

As the project moves through the Conditional Use Permit process, residents remain defiant. Webb speaks for many: “We will not let them take down our forest. We will stand as a community in protecting our forest.”