The term mental illness can conjure up images of disease, a broken brain and unstable and nonfunctional people. In western culture a psychological diagnosis can lead to a lifetime of medications and isolation by family members and society as a whole.

“Fifty percent of people in prisons are mentally ill, and between 30 to 40 percent of homeless people,” filmmaker and photographer Phil Borges said. After 25 years of documenting indigenous cultures, Borges has witnessed a healthier, more humane way of helping people cope with what he calls a mental, emotional crisis, or psychotic break.

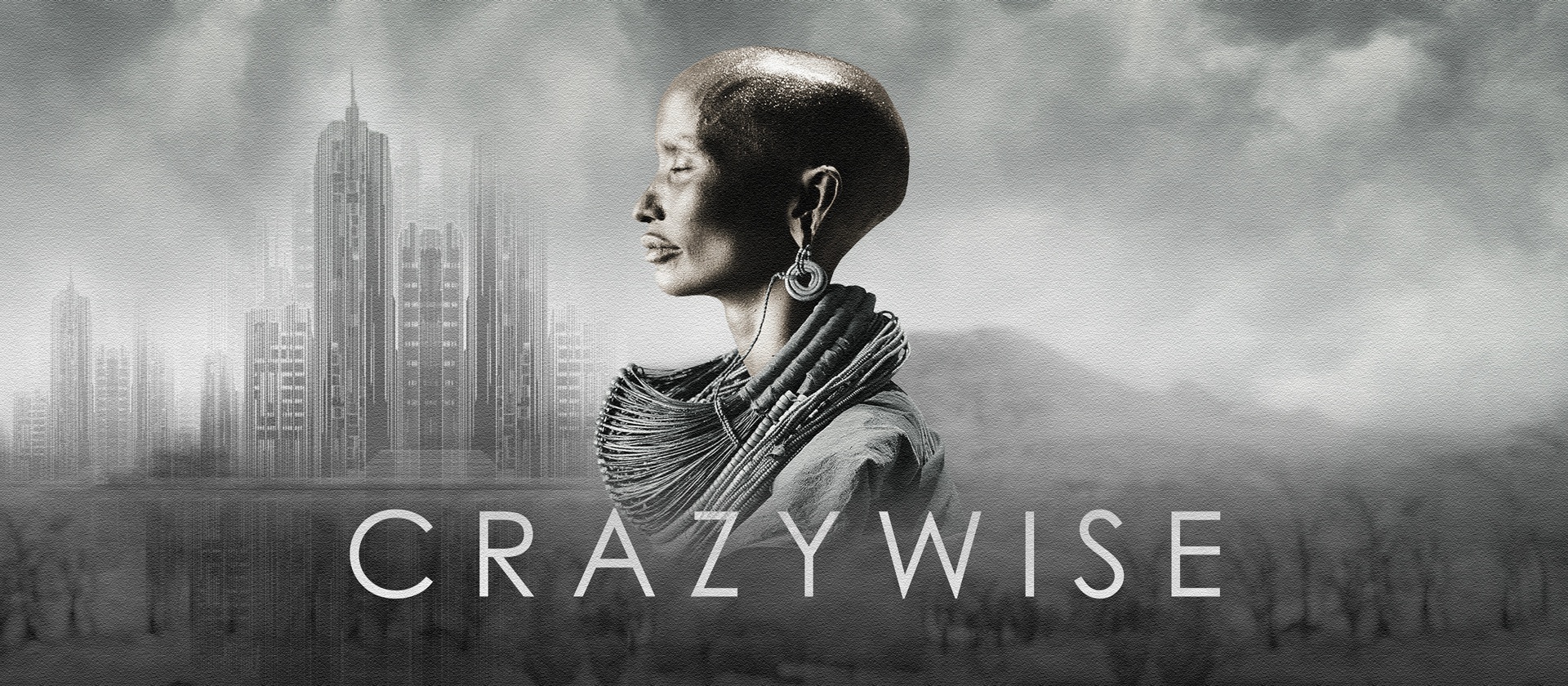

“Crazywise” a documentary directed by Phil Borges and Kevin Tomlinson, examines indigenous cultures’ reaction to people in mental crises as opposed to a western response. On May 19, from 7-8:30 p.m. a fundraiser will be held at Brickworks to help raise funds for the completion of the documentary. Excerpts from the film will be shown, and Borges will talk about the film. All tax deductible donations through the Northwest Film Forum, an umbrella nonprofit sponsoring the project, will go toward the cost of music, composition, animation of graphics, and distribution of the film, according to Julee Geier, co-producer and head of public relations.

The concept for “Crazywise” was formed for Borges while documenting the Tibetan culture more than 20 years ago. He watched a young Tibetan monk, known as “a kuten” or spiritual protector, also known as the Dalai Llama’s Oracle, go into a ceremonial trance. The ceremony began with chanting, prayers and drums. The Oracle’s eyes rolled back in his head, his face turned red and he began speaking in a high pitched voice. His assistants began writing down every word the Oracle uttered. Borges calls it one of the most fascinating events he has ever seen.

Borges attended an interview with the Oracle the following day. During that interview the young monk described how he became a kuten. As a boy, the Oracle experienced intense terrible dreams, he began hearing voices, suffered from anxiety, panic attacks, and felt electrical shocks though his body. The monks did not shun or isolate the young boy, instead, they told him he had a gift, and he was mentored.

As Borges documented other indigenous cultures, he began asking who their healers were. The more shamans, healers and spiritual leaders he spoke to, the more their stories sounded the same; they had all heard voices, had hallucinations, anxiety, and were consequently taken under someone’s wing. Indigenous cultures, Borges said, are not frightened by mental illness. Instead these cultures are open and supportive of someone in a mental crisis.

In contrast, the U.S., Borges says, “straps a person having a mental crisis either in a cop car or an ambulance. If its in a cop car, they are often afraid they are in trouble and have done something wrong. They can be left for up three to four hours, until a doctor is available, then they are injected with medications,” he added.

Along with interviewing shamans, healers, anthropologists, and psychiatrists, the film follows two people with mental illness in the U.S., Adam and Ekhaya, who were rejected from their families, and spent time on the streets.

“I hope this film ends up showing people that they are okay,” Adam says in “Crazywise.”

Ekhaya explains in “Crazywise,” how she struggled to find any meaning through her crisis. It was through Baltic Street, a peer to peer mental support center that she was able to find meaning and self worth, “Once you’ve been diagnosed…, you kind of lose hope. You think this is what I’m going to be doing for the rest of my life. I might collect Social Security or disability… Through Baltic Street I was able to find a job,” said Ekyaha, now a peer counselor herself, assisting others to navigate what she herself survived.

Borges is cautious to add that everyone’s situation is different, there is no one size fits all approach, nor does he want to romanticize indigenous cultures, they have their own issues, he says, but they do have something to teach us about mental health.

“I don’t want to romanticize mental illness, it is terrible, frightening, dark night of the soul,” said Borges. “But if it can be navigated and it’s possible to come out on the other side with a better connection with humanity.”

Getting help

For anyone experiencing, or knows anyone experiencing, a mental or emotional crisis, Borges says, get support. If support is not possible from family members, look to other social networks. Try to find a mentor who has been through it, who understands. Taking care of one’s physical body; sleep, exercise and eating right is also critical. Borges says the brain can’t function without those basics. Pay attention to doctor’s giving support, if they do not believe in recovery, try to find a doctor who does.

“Medication has its place,” Borges said. “I am not against medications, but it’s a band aid.”

Peer to peer centers are opening up all over the country, which use a support network that involves mentor-ship The National Alliance on Mental Health in Seattle states on its website, www.nami.org/Find-Support/NAMI-Programs/NAMI-Peer-to-Peer, that it offers 10 free peer to peer sessions.