For 42 years the canoe called Kwigwatsi transported people across the waters surrounding the San Juan Islands. Its passengers varied. Frequently it carried students coming and going from Camp No’rwester, other occasions, elders and families heading to potlatches.

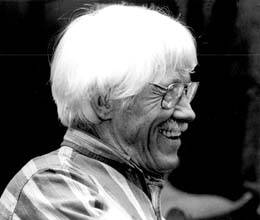

On Aug. 8, Bill Holm, carver of that 35-foot boat, spoke to a full house at Brickworks, describing the history of coastal canoes and the story of Kwigwatsi.

“The amount of wood it takes to build one of these canoes is incredible,” Holm said, explaining it requires eight times the volume of wood as the volume of the canoe.

His presentation was an Art As Voice interpretive program that accompanies San Juan Islands Museum of Art’s exhibits. Kwigwatsi is part of their current show, “Emergence, Legendary and Emerging First Nations Artists.”

Curator Emeritus of Northwest Indian art at the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture, Holm devoted his life to perpetuating the traditions of Northwest Coast First Nations. He has been honored by First Nations people in return, with certificates of appreciation from the Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshia as well as receiving many honorary names, signifying an acceptance into the First Nations community.

Kwigwatsi was born in 1968 at Camp Nor’wester on Lopez Island and made from a massive red cedar tree Holm bought from a Bellingham lumber company, which he then hauled to the San Juans.

Holm and his crew started by shaping the hull with axes and chisels with the addition of the non-traditional chainsaw.

“Here I am with the magic machine,” he said as an image of him utilizing the modern technology appeared on the screen. Next came images of the crew using long swift pendulum ax strokes to carve out the hull’s curves. If the strokes were too deep, the sides of the boat would not be even.

“We’re getting there,” said Holm as the canoe slowly evolved from the cedar, and a giggle erupted from the crowd. There was clearly a long way to go. Holes were drilled through the canoe and immediately plugged, the traditional way of measuring the thickness of the sides. Once that task was completed, the future canoe was turned upside down, enabling the crew to work on the interior, chipping rows lengthwise at the end of plugs for consistent thickness.

When asked why red cedar was the favored tree, Holm responded,“Red cedars are big, and the wood is light and durable.”

He explained that spruce was also used, especially where red cedars were not available. As the documentary progressed, the canoe was taken out for a maiden voyage, and painted in the traditional colors of red black and white, with an eagle head in the bow block.

Unfortunately in 2011, while awaiting repairs, a tree fell across the middle of Kwigwatsi, crushing the 42-year-old canoe beyond repair.

“That’s enough of that,” said Holm, moving on to discuss the history of native west coast canoes.

Canoes like Kwigwatsi once frequented the waters along the coast of Washington all the way to Alaska. Holm presented photos of the variety of fleets.

“These drawings were done by explorers,” Holm said. “Some of the images are more accurate than others.”

The boats were used for everything from gill netting, fishing, whaling, racing and transportation to potlatches and other ceremonies and battle. War canoes were designed with a long, high protective bow.

“Why are the bows raised?” one crowd member asked.

Holm proceeded to tell the story how he was using Kwigwatsi to carry students to Camp No’rwester. He and the crew encountered rough waters, one large wave in particular. “Don’t worry, I trust your canoe,” said one of the passengers.

Kwigwatsi, with raised bow, rose up into and separated the waves high water, and continued on its journey, carrying passengers and crew safely to their destination.

According to Holm, simple masts were used prior to the arrival of Europeans. Some canoes had a single sail, others were equipped with a pair that when full almost looked like dragon wings rising out of the interior. Kwigwatsi had a pair of sails and Holm showed pictures of it flying through the sea.

Amongst the historical drawings, there was a dramatic scene with mountains rising up in the background. The sky is darkening, and a Native American is standing toward the bow of his canoe, watching a large European ship in the distance.

“You can almost feel him thinking ‘There goes the neighborhood,’” Holm said, causing the audience to laugh.

Other drawings showed an attack between Europeans and First Nations that took place in the Strait of Juan De Fuca in 1792. There were images of the assorted styles, shapes, and sizes of traditional canoe as well as the intricate paddles that were used.

“You survived,” said Holm in closing, teasing the entranced crowd.

For more information about the art and culture of the Pacific Northwest First Nations, visit the San Juan Island Museum of Art’s “Emergence, Legendary and Emerging First Nations Artists.” which runs until Sept. 4. Museum hours run from 11 a.m. to 6 p.m. Thursdays through Mondays.