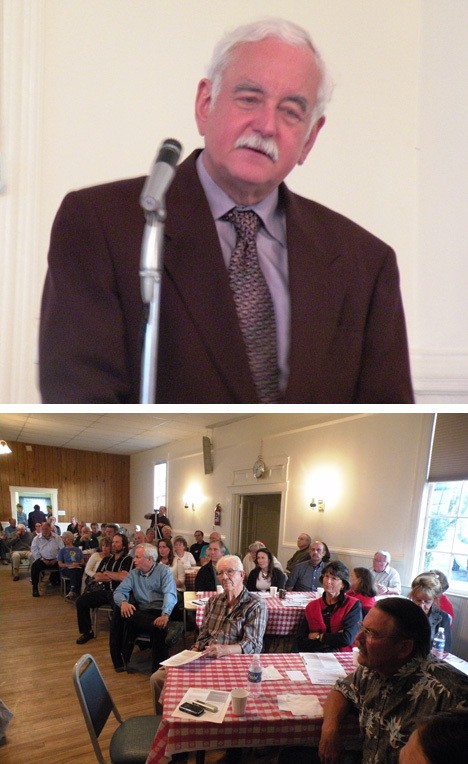

The Citizens Alliance for Property Rights hosted a presentation Tuesday by state Supreme Court Justice Richard Sanders concerning private property rights and the courts.

Sanders was as big a hit as the tri tip dinner and the camaraderie which filled the Grange Hall to capacity.

The Citizens Alliance for Property Rights — also known as CAPR — hosted the presentation as part of its series on the proposed update to the county’s Critical Areas Ordinance. The most debated issue is the minimum distance that new development should be set back from the shoreline. State regulations and some scientists have suggested a need to increase development setbacks to as much as 150 or 200 feet from the shoreline. Real estate and development interests in San Juan County say those setbacks are extreme and that such requirements could cost the county millions of dollars in lost property value and property taxes.

Since joining the Supreme Court in 1995, Sanders has become recognized for his published opinions. As a private practitioner, Sanders regards protection of constitutionally guaranteed liberties as the first duty of the court. “The court must protect all the legal rights of all the citizens who come before it, all the time. We have no second-class citizens,” he said.

The topic of eminent domain — the taking of private property for government or public use — began with a quote from the Washington State Constitution: “No person shall be deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law. Private property shall not be taken for private use. No private property shall be taken or damaged for public or private use without just compensation having been first made.”

The Connecticut Constitution also provides “The property of no person shall be taken for public use, without just compensation therefor.” But that, apparently, didn’t help Susette Kelo. Her restored pink house in New London was acquired by eminent domain by the city so it and neighboring properties could be redeveloped. Kelo sued; the Connecticut Supreme Court ruled 5–4 that the general benefits a community enjoyed from economic growth qualified such redevelopment plans as a permissible “public use” under the takings clause of the Fifth Amendment.

Some members of CAPR say the proposed setbacks in San Juan County would be tantamount to taking property by eminent domain.

“We support equitable and scientifically sound land-use regulations that do not force small groups of private property owners to pay for public benefits enjoyed by all,” CAPR President Frank Penwell said.

“We believe that private property owners are far better stewards of this earth than collectivist central planners are. We want our children and grandchildren to be able to enjoy our land and not have to move elsewhere in order to afford a home of their own. Our group wants courts to not misinterpret laws protecting property rights because they are very clear in their meaning.”

Penwell described CAPR as “a non-partisan organization. Our members are from all politcal parties. What we have in common is that we support liberty over tyranny.”

During the question and answer period, other examples of local government policies clashing with property rights were raised. One islander who owns property adjacent to Pelindaba Lavender Farm said he received a higher property assessment because he had a potential view of the lavender farm. He said he had no view at all because of trees bordering his property.

According to the property owner, the assessor’s office said that if he cut the trees down, he would have a view so therefore his property was valued based upon that potential view.

The property owner said he had to get a letter from a federal agency stating that his land was a wetland and that it was against the law for him to cut those trees.