San Juan County staff and residents are brainstorming local ways to protect orcas, just as a new report predicts their possible demise within a century.

According to a study, released in October in the journal Scientific Reports, there is a 25 percent chance the local orcas, known as Southern resident killer whales, will disappear in 100 years.

That is, unless their main food source of Chinook salmon increases, while vessel noise decreases to allow them to locate that food. Orcas find food by listening to underwater vibrations reflecting against objects.

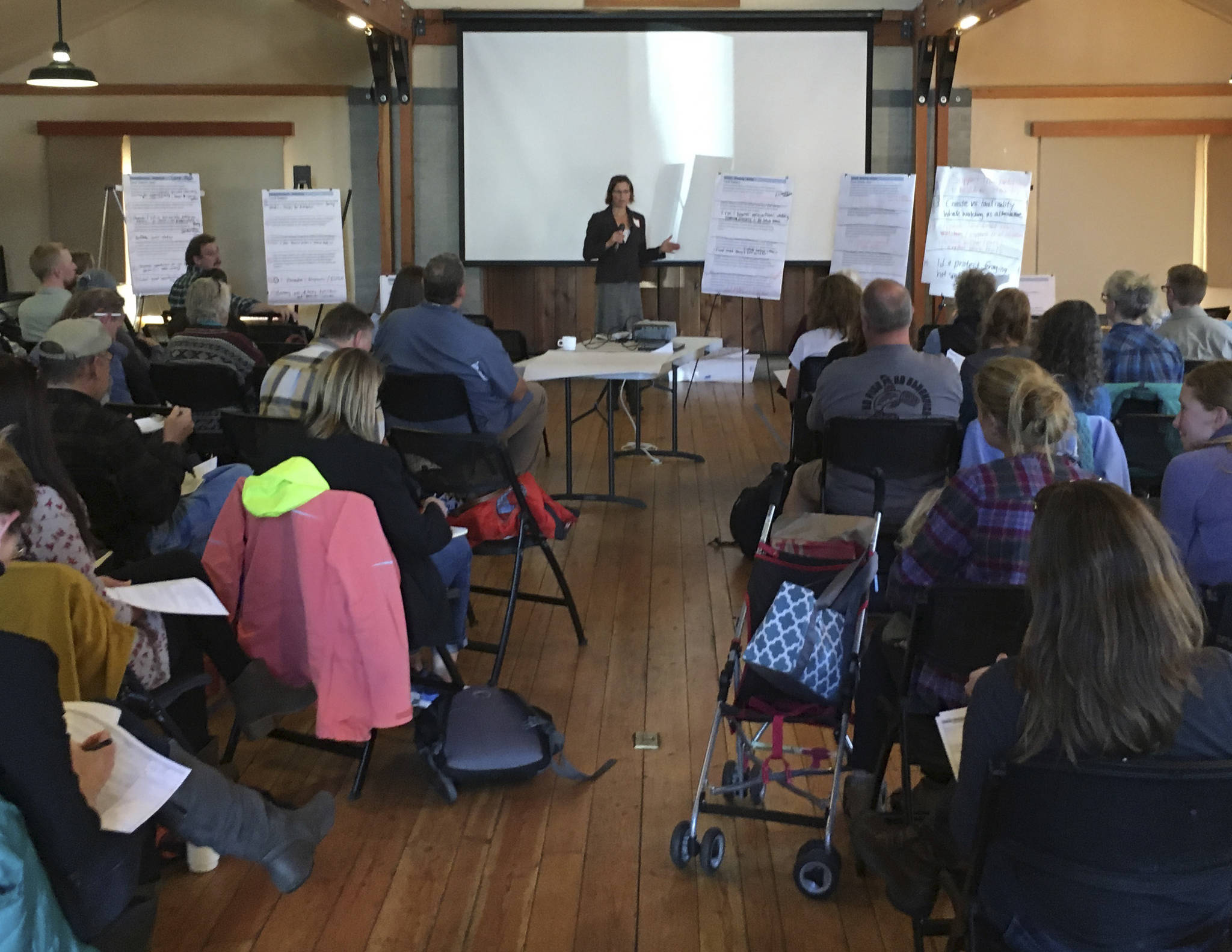

Possible solutions against these known threats were discussed at a workshop, sponsored by the San Juan County Marine Resources Committee and Public Works on Friday, Oct. 27 at Brickworks. Another workshop was held two days later in the same location, sponsored by a group of local whale researchers and advocates called CALF, which stands for Community Action Look Forward.

Both workshops’ goal: find solutions that can be done locally.

“This isn’t about pointing fingers,” said San Juan County Environmental Resources Manager Kendra Smith, who coordinated the county meeting and attended both. “It’s about individual action we can do right now.”

The urgency comes from 2016 population counts, putting the local orcas at their lowest numbers in decades at 78. In the 90s there were close to 100.

At the Oct. 27 meeting, about 100 stakeholders in the protection of the whales were invited by county staff to attend a roughly three-hour workshop. This included representatives from local, state and federal government agencies, whale watch companies and individuals who support orca protection. Staff prepared solutions gathered from roughly 450 responders of an online county survey on orca protection. Attendees edited the solutions and added more.

The most popular possible solutions included:

• Implementing lower speeds in county waters for all boats during the summer to lower vessel noise.

• Encouraging fisheries managers to reduce Chinook harvest in the county.

• Protecting local Chinook forage fish habitats.

• Limiting the number of whale watch boat permits in the summer and promoting land-based whale watching to limit invasive interactions.

• Banning the use of toxic fertilizers and pesticides in the county, which run off into the ocean.

• Charging an extra fee for whale watch boat customers and using funds for orca recovery.

About a third of the attendees from the county meeting made it to the public CALF workshop, as well as about 40 additional participants. CALF attendees discussed similar issues, like how to prevent pollutants in island stormwater drains from reaching the orcas’ waters, as well as promoting products, like household cleaners, that are safe for orcas if they end up in the ocean.

Both groups also considered the possibility of expanding a federal overfishing act to include an annual Chinook quota for the orcas. The 1976 Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act sets aside fish for commercial and recreational fishers and tribes, but not orcas, said CALF workshop facilitator Deborah Giles, Ph.d. County government and residents could encourage the federal government to change the legislation.

“We, as whale advocates, are wanting to talk to the fishing community and the tribal communities to open a dialogue about the importance of recovery of the salmon for them and the whales,” said Giles, a researcher and lecturer at the University of Washington Friday Harbor Labs.

Southern resident killer whales mainly eat Chinook, as opposed to other salmon or mammals, like similar species eat. Chinook from the Columbia River, as well as Southern resident killer whales, have been listed under the Endangered Species Act since 2005.

Despite their endangered status, reform can often take time. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration staff have been working on a petition to extend the whale’s critical habitat off the coast of Washington to California since 2014. Michael Milstein, a media representative with NOAA’s West Coast Region said a proposal for the extension may be released next year, but there are no definite dates as to when changes will be made.

That is the federal agency’s main focus, he said, not the late 2016 petition to ban motorized vessels along the entire west side of San Juan Island, where orcas often feed.

“We have set this petition aside for a moment while we finish the critical habitat process,” said Milstein.

Yet, the study published in Scientific Reports — with contributions by locals Ken Balcomb, founder of the Center for Whale Research, and Giles, who worked with the center — states a clear solution to orca deaths.

The study concludes that 30 percent more Chinook is needed, than today’s average counts, to maintain the species. If vessels noise decreases by half, then 15 percent more is needed. So what’s the holdup? While government bureaucracy accounts for some stalls, Smith also noted that a century’s deadline can be difficult to visualize.

“I think its a challenge in our culture to consider the impact of our actions today on seven generations ahead,” she said. “Change is hard, and it will likely require adjusting our lifestyle and livelihoods for the benefit of other species. I certainly don’t want to be part of the generation that stood on the sidelines.”

Smith and her department’s staff will compile a report of the county workshop solutions to present to the county council by mid-December. CALF members plan to hold a workshop in Victoria with fishing communities to discuss the Magnuson-Stevens Act in the upcoming months. To receive CALF workshop updates, email Giles at giles7@uw.edu.

Read the study, published in Scientific Reports, below.

“Evaluating anthropogenic threats to endangered killer whales to inform effective recovery plans”